From Boydell and Brewer:

Miracles of the Virgin: Law and Jewishness in Marian Legends

A blog for those who attended the conference on 'York 1190' in March 2010 at the University of York.

York 1190: Jews and Others in the Wake of Massacre was organised by Sarah Rees Jones and Sethina Watson of the Centre for Medieval Studies and the Department of History.

The conference was supported by the British Academy, the Jewish Historical Society of England and the Royal Historical Society. The Borthwick Institute republished the essays of Barrie Dobson on anglo-jewish history for the occasion: The Jewish Communities of Medieval England . We are publishing a collection of essays relating to the theme of the conference and developing further related research projects.

The conference was supported by the British Academy, the Jewish Historical Society of England and the Royal Historical Society. The Borthwick Institute republished the essays of Barrie Dobson on anglo-jewish history for the occasion: The Jewish Communities of Medieval England . We are publishing a collection of essays relating to the theme of the conference and developing further related research projects.

Friday, 17 December 2010

Wednesday, 15 December 2010

New Graduate Student Medieval Studies Journal at the CUNY Graduate Center

From Ethan Zadoff:

The Medieval Studies Certificate Program (MSCP) and Pearl Kibre Memorial Study at the CUNY Graduate Center has started a new gradate student journal.

We are currently putting together our first volume based on last year's annual MSCP conference theme titled "Intimacy: Family, Fealty and Friendship in Middle Ages" and we are soliciting submissions from graduate students in fields related to medieval studies for our inaugural edition. We are planning a fairly aggressive time frame for the publication of the first volume and as such, if you wish to submit your work please do so no later than Friday January 7 to allow for a full editorial process to take shape.

We also welcome reviews of recently published books. The first volume will be an online volume only and we would like submissions to be no longer than forty-five double spaced pages.

If you are interested in submitting a paper or book review or if you have any questions please contact Ethan Zadoff at Ezadoff@gc.cuny.edu

The Medieval Studies Certificate Program (MSCP) and Pearl Kibre Memorial Study at the CUNY Graduate Center has started a new gradate student journal.

We are currently putting together our first volume based on last year's annual MSCP conference theme titled "Intimacy: Family, Fealty and Friendship in Middle Ages" and we are soliciting submissions from graduate students in fields related to medieval studies for our inaugural edition. We are planning a fairly aggressive time frame for the publication of the first volume and as such, if you wish to submit your work please do so no later than Friday January 7 to allow for a full editorial process to take shape.

We also welcome reviews of recently published books. The first volume will be an online volume only and we would like submissions to be no longer than forty-five double spaced pages.

If you are interested in submitting a paper or book review or if you have any questions please contact Ethan Zadoff at Ezadoff@gc.cuny.edu

Tuesday, 23 November 2010

Friday, 24 September 2010

New explanation for the Expulsion

Coming Soon!!!!!

The political economy of expulsion: the regulation of Jewish money lending in medieval England.

http://www.springerlink.com/content/p700t2q4216158q4/

This paper develops an analytic narrative examining an institution known as ‘The Exchequer of the Jewry’. The prohibition on usury resulted in most money lending activities being concentrated within the Jewish community. The king set up the Exchequer of the Jewry in order to extract these monopoly profits. This institution lasted for almost 100 years but collapsed during the second part of the thirteenth century. This collapse resulted in the expulsion of the Anglo-Jewish population. This paper provides a rational choice account of the institutional trajectory of the Exchequer of the Jewry. This account explains why it ultimately failed to provide a suitable framework for the development of capital markets in medieval England.

Forthcoming: Constitutional Political Economy, vol. 24, number 4. December 2010.

In a new explanation of the Expulsion of 1290 this paper leads with the idea that the rise of parliament led to deterioration in the position of England’s Jewish population. The battle against the Jews was a part of a thirteenth century power struggle. A brick in state craft and what Carpenter would call a ‘Struggle for Mastery’. The Exchequer of the Jews was jettisoned at the end of the thirteenth century because it was not politically incentive compatible. From a longer term perspective, the Exchequer of the Jewry looks like an institutional ‘false start’. It failed to result in the development of broad or deep capital markets.

The Exchequer of the Jewry was an institution designed to maximize the amount of rent that could be extracted from the prohibition against usury a veritable ‘engine of extortion’ as Charles Gross would have called it. Koyama argues that the ultimate demise of this institution came not because these rents were dissipated (though he admits some dissipation did occur), but because the political incentives facing the king changed. He returns to the almost lost but prophetic words of J R Green (1877 !!) Green observed that it ‘was in the Hebrew coffers that the Norman kings found strength to hold their baronage at bay’ (p123). He argues that the kings after Edward I would not have access to these coffers, and as a result parliament would be in a better position to hold them to account.

Mark Koyama is about to join the Economics Department at the University of York.

The political economy of expulsion: the regulation of Jewish money lending in medieval England.

http://www.springerlink.com/content/p700t2q4216158q4/

This paper develops an analytic narrative examining an institution known as ‘The Exchequer of the Jewry’. The prohibition on usury resulted in most money lending activities being concentrated within the Jewish community. The king set up the Exchequer of the Jewry in order to extract these monopoly profits. This institution lasted for almost 100 years but collapsed during the second part of the thirteenth century. This collapse resulted in the expulsion of the Anglo-Jewish population. This paper provides a rational choice account of the institutional trajectory of the Exchequer of the Jewry. This account explains why it ultimately failed to provide a suitable framework for the development of capital markets in medieval England.

Forthcoming: Constitutional Political Economy, vol. 24, number 4. December 2010.

In a new explanation of the Expulsion of 1290 this paper leads with the idea that the rise of parliament led to deterioration in the position of England’s Jewish population. The battle against the Jews was a part of a thirteenth century power struggle. A brick in state craft and what Carpenter would call a ‘Struggle for Mastery’. The Exchequer of the Jews was jettisoned at the end of the thirteenth century because it was not politically incentive compatible. From a longer term perspective, the Exchequer of the Jewry looks like an institutional ‘false start’. It failed to result in the development of broad or deep capital markets.

The Exchequer of the Jewry was an institution designed to maximize the amount of rent that could be extracted from the prohibition against usury a veritable ‘engine of extortion’ as Charles Gross would have called it. Koyama argues that the ultimate demise of this institution came not because these rents were dissipated (though he admits some dissipation did occur), but because the political incentives facing the king changed. He returns to the almost lost but prophetic words of J R Green (1877 !!) Green observed that it ‘was in the Hebrew coffers that the Norman kings found strength to hold their baronage at bay’ (p123). He argues that the kings after Edward I would not have access to these coffers, and as a result parliament would be in a better position to hold them to account.

Mark Koyama is about to join the Economics Department at the University of York.

Wednesday, 15 September 2010

Congratulations Anthony!

Feeling Persecuted : Christians, Jews and Images of Violence in the Middle Ages

One of the most fascinating aspects of medieval culture was the imaginary violence Christians believed that Jews carried out, and the subsequent violence Christians committed against Jews. Many Christians believed that Jews committed crimes against Christian children, Christ's body, and the Eucharist, leading them to conclude that Jews were out to destroy their religion and way of life. They retaliated with expulsions, riots and murders that systematically denied Jews the right to religious freedom and peace. In Feeling Persecuted: Christians, Jews, and Images of Violence in the Middle Ages, Anthony Bale explores the Christian pain and fear so often blamed on Jews, and how the imagined violence caused Christians to retaliate with crushing violence of their own. Through close reading of a wide range of European sources, Bale exposes the spiritual and intellectual benefits of imagined Jewish violence, and how the images of Christian suffering and persecution were central to medieval ideas of love, belonging and home life. These images and texts even expose a surprising practice of recreational persecution, and show that the violence perpetrated against medieval Jews was far from simple anti-Semitism and was in fact a complex part of medieval life and culture. Feeling Persecuted reveals the culture of imagined violence and tracks its far-reaching consequences into modern Jewish-Christian relations. Anthony Bale's comprehensive look at poetry, drama, visual culture, theology and philosophy make Feeling Persecuted an important resource for anyone interested in the history of Christian-Jewish relations, and the impact of past events on modern culture.

About the Author

Anthony Bale is Professor of English and Medieval Cultures at Birbeck College, University of London. He is the author of The Jew in the Medieval Book: English Antisemitisms 1350-1500 (2006).

One of the most fascinating aspects of medieval culture was the imaginary violence Christians believed that Jews carried out, and the subsequent violence Christians committed against Jews. Many Christians believed that Jews committed crimes against Christian children, Christ's body, and the Eucharist, leading them to conclude that Jews were out to destroy their religion and way of life. They retaliated with expulsions, riots and murders that systematically denied Jews the right to religious freedom and peace. In Feeling Persecuted: Christians, Jews, and Images of Violence in the Middle Ages, Anthony Bale explores the Christian pain and fear so often blamed on Jews, and how the imagined violence caused Christians to retaliate with crushing violence of their own. Through close reading of a wide range of European sources, Bale exposes the spiritual and intellectual benefits of imagined Jewish violence, and how the images of Christian suffering and persecution were central to medieval ideas of love, belonging and home life. These images and texts even expose a surprising practice of recreational persecution, and show that the violence perpetrated against medieval Jews was far from simple anti-Semitism and was in fact a complex part of medieval life and culture. Feeling Persecuted reveals the culture of imagined violence and tracks its far-reaching consequences into modern Jewish-Christian relations. Anthony Bale's comprehensive look at poetry, drama, visual culture, theology and philosophy make Feeling Persecuted an important resource for anyone interested in the history of Christian-Jewish relations, and the impact of past events on modern culture.

About the Author

Anthony Bale is Professor of English and Medieval Cultures at Birbeck College, University of London. He is the author of The Jew in the Medieval Book: English Antisemitisms 1350-1500 (2006).

The Jews of York

Tuesday, 14 September 2010

First Prize for First Submission!

"Dehumanizing the Jew at the Funeral of the Virgin Mary” - the first contribution to our proposed volume.

Image:

Lady Chapel Window, south side of the choir clerestory, York Minster

Monday, 23 August 2010

Bibliography for medieval Anglo-Jewry

I was very glad when returning to write up my 1190 article to find the following on the JHSE website:

A Selective Bibliography of Medieval Anglo-Jewry to 1290

It is selective - and I thought it might be fun (and useful) to add to it? Then I realised this would be a large task, especially if we extended it to include the period up to 1500. Here are some suggestions

HYAMS Paul R. , ‘‘The Jews in medieval England, 1066-1290’ in Haverkamp, Alfred; Vollrath, Hanna (ed.), England and Germany in the High Middle Ages : in honour of Karl J. Leyser (Studies of the German Historical Institute London) (Oxford and London: Oxford University Press and the German Historical Institute, 1996) : 173-92

Plus Journal of Jewish Studies, 1976

BALE Anthony Paul, The Jew in the Medieval Book; English antisemitisms 1350-1500 (Cambridge, 2006)

Plus at least six other publications

COHEN Jeffrey Jerome, ‘The Flow of Blood in Medieval Norwich’, Speculum 79:1 (2004) 26-65

BARTLET, Suzanne, Licoricia of Winchester: Marriage, Motherhood and Murder in the Medieval Anglo-Jewish Community (Vallentine Mitchell, 2009)

HOYLE, Victoria, 'The bonds that bind : money lending between Anglo-Jewish and Christian women in the plea rolls of the Exchequer of the Jews 1218-1280' Journal of Medieval History 34:2 (2008) 119-29 - special issue of the journal on Conversing With the Minority: Relations Among Christian, Jewish and Muslim Women in the High Middle Ages

among many others

What are your recommendations?

A Selective Bibliography of Medieval Anglo-Jewry to 1290

It is selective - and I thought it might be fun (and useful) to add to it? Then I realised this would be a large task, especially if we extended it to include the period up to 1500. Here are some suggestions

HYAMS Paul R. , ‘‘The Jews in medieval England, 1066-1290’ in Haverkamp, Alfred; Vollrath, Hanna (ed.), England and Germany in the High Middle Ages : in honour of Karl J. Leyser (Studies of the German Historical Institute London) (Oxford and London: Oxford University Press and the German Historical Institute, 1996) : 173-92

Plus Journal of Jewish Studies, 1976

BALE Anthony Paul, The Jew in the Medieval Book; English antisemitisms 1350-1500 (Cambridge, 2006)

Plus at least six other publications

COHEN Jeffrey Jerome, ‘The Flow of Blood in Medieval Norwich’, Speculum 79:1 (2004) 26-65

BARTLET, Suzanne, Licoricia of Winchester: Marriage, Motherhood and Murder in the Medieval Anglo-Jewish Community (Vallentine Mitchell, 2009)

HOYLE, Victoria, 'The bonds that bind : money lending between Anglo-Jewish and Christian women in the plea rolls of the Exchequer of the Jews 1218-1280' Journal of Medieval History 34:2 (2008) 119-29 - special issue of the journal on Conversing With the Minority: Relations Among Christian, Jewish and Muslim Women in the High Middle Ages

among many others

What are your recommendations?

Wednesday, 18 August 2010

Stones, Houses, Jews, Myths

Are there more myths associated with medieval Jewish history than other kinds? Probably not. But one of them is that all medieval jews lived in stone houses and that all stone houses belonged to medieval jews. (I exaggerate but only a very little).

Are there more myths associated with medieval Jewish history than other kinds? Probably not. But one of them is that all medieval jews lived in stone houses and that all stone houses belonged to medieval jews. (I exaggerate but only a very little).Not true! Either way around.

The map shows the spread of stone houses recorded in documents across the city of York in the twelfth, thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Yep - they were to be found in all the major streets and in both the city centre and its suburbs. Only two fragments of such houses survive. One -in Stonegate -was occupied by a canon of York Minster, who I guess was probably a Christian ;-). I recently saw somebody write that because it was stone it must have been Jewish - ach! The other we don't know for sure - but from the records we can say that most of these houses were not owned or occupied by Jews - but by all kinds of successful artisans and merchants, clerics, officials, farmers. For more discussion of why, how etc see an article by yours truly in Medieval Domesticity ed Kowaleski and Goldberg.

For more on Jews and stones see Here and I am sure elsewhere at In The Middle. Really - our persistent association of stones and Jews speaks to me of retrospective judgements we want to make about medieval Jews and their place in society.

Saturday, 14 August 2010

1190 Book (update and reminder)

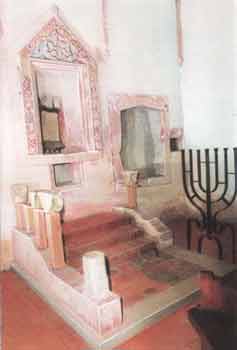

A quick update and reminder for those contributing to the volume. If anything seems amiss please email me. (Image: medieval synagogue in Sopron, Hungary)

The York Massacre of 1190 in context: Reassessing relations between Jews and others in medieval England

The mass suicide and murder of the men, women and children of the Jewish community in York on 16 March 1190 is one of the most scarring events in the history of Anglo-Judaism, and an aspect of England’s medieval past which is widely remembered around the world. The York massacre was in fact only one of a series of attacks on local communities of Jews across England in 1189-90. These were violent expressions of wider new constructs of the nature of Christian and Jewish communities and they were also the targeted outcries of local townspeople, whose emerging urban polities were enmeshed within swiftly developing structures of royal government.

This collection of essays will use the events of 1189-90 as a lens through which to reassess the rapid changes which were reconstructing communities and their relationship to royal and ecclesiastical government both locally and in national and European contexts. It will take advantage of the substantial amount of new work which has been done on twelfth-century England, notably on government and local power, ethnic identity, relationships with Europe, the development of distinct regional identities and new intellectual and religious models of community and pastoral care. Our aim is to consider the massacre as central to the narrative of English history around 1200 as well as that of Jewish history.

Two conversations run strongly through the entire collection. One is on the role of narrative in shaping events and our perception of them. The other is the degree of convivencia between Jews and Christians and consideration of the circumstances and processes through which neighbours became enemies and victims.

Contributors to the volume include many of the leading scholars working on English history and literature in the high middle ages including those most closely associated with studies of medieval anglo-jewry. We are also pleased to include the work of several younger scholars, relatively new to the field.

Sethina Watson, University of York, Introduction

Sarah Rees Jones, University of York

York in the Twelfth Century

Paul Hyams, Cornell University

Faith, Fealty, Lordship, and Jewish Infideles in twelfth-century England

Hugh Doherty, University of Oxford,

The sheriffs of Yorkshire and the massacre of 1190

Joe Hillaby

Prelude and Postscript to the York Massacre: Attacks in East Anglia and Lincolnshire, 1190

Nicholas Vincent, University of East Anglia

Richard I: the new Titus

Alan Cooper, Colegate University

1190: Context and Aftermath. Longbeard’s Uprising in London in 1196

Heather Blurton, University of California Santa Barbara

‘Dies Aegyptiae’: From Passion to Exodus in the Representation of 12th Century Jewish-Christian Relations

Ethan Zadoff and Pinchas Roth, CUNY and Hebrew University Jerusalem

England and the Talmudic community of medieval Europe

Eva de Visscher, University of Oxford

Jewish teachers, Christian pupils: the transmission of rabbinic learning from Jewish to Christian scholars in medieval England

Anna Abulafia, University of Cambridge

Notions of Jewish service in twelfth and thirteenth-century England.

Robert Stacey, University of Washington

The Massacres of 1189-90 and the Origins of the Jewish Exchequer, 1186-1226

Robin Mundill, Glenalmond College, Perth

The Legacy of the Archa System after 1216.

Matthew Mesley, University of Exeter

Cures and Conversions: The ‘Jewish Pilgrim topos’ in 13th century miracle accounts.

Carlee Bradbury, Radford College

“Monstrous contact: the Jew at the funeral of the Virgin Mary.”

Hannah Johnson, Pitt University, US

Massacre and Memory: The New Intellectual Politics of Remembering Jewish Martyrdom”

Jeffrey Cohen, George Washington University, US

The Future of the Jews of York

Anthony Bale, Birkbeck College, London

Text, Memory, Event: The Aesthetics of Persecution

The York Massacre of 1190 in context: Reassessing relations between Jews and others in medieval England

The mass suicide and murder of the men, women and children of the Jewish community in York on 16 March 1190 is one of the most scarring events in the history of Anglo-Judaism, and an aspect of England’s medieval past which is widely remembered around the world. The York massacre was in fact only one of a series of attacks on local communities of Jews across England in 1189-90. These were violent expressions of wider new constructs of the nature of Christian and Jewish communities and they were also the targeted outcries of local townspeople, whose emerging urban polities were enmeshed within swiftly developing structures of royal government.

This collection of essays will use the events of 1189-90 as a lens through which to reassess the rapid changes which were reconstructing communities and their relationship to royal and ecclesiastical government both locally and in national and European contexts. It will take advantage of the substantial amount of new work which has been done on twelfth-century England, notably on government and local power, ethnic identity, relationships with Europe, the development of distinct regional identities and new intellectual and religious models of community and pastoral care. Our aim is to consider the massacre as central to the narrative of English history around 1200 as well as that of Jewish history.

Two conversations run strongly through the entire collection. One is on the role of narrative in shaping events and our perception of them. The other is the degree of convivencia between Jews and Christians and consideration of the circumstances and processes through which neighbours became enemies and victims.

Contributors to the volume include many of the leading scholars working on English history and literature in the high middle ages including those most closely associated with studies of medieval anglo-jewry. We are also pleased to include the work of several younger scholars, relatively new to the field.

Sethina Watson, University of York, Introduction

Sarah Rees Jones, University of York

York in the Twelfth Century

Paul Hyams, Cornell University

Faith, Fealty, Lordship, and Jewish Infideles in twelfth-century England

Hugh Doherty, University of Oxford,

The sheriffs of Yorkshire and the massacre of 1190

Joe Hillaby

Prelude and Postscript to the York Massacre: Attacks in East Anglia and Lincolnshire, 1190

Nicholas Vincent, University of East Anglia

Richard I: the new Titus

Alan Cooper, Colegate University

1190: Context and Aftermath. Longbeard’s Uprising in London in 1196

Heather Blurton, University of California Santa Barbara

‘Dies Aegyptiae’: From Passion to Exodus in the Representation of 12th Century Jewish-Christian Relations

Ethan Zadoff and Pinchas Roth, CUNY and Hebrew University Jerusalem

England and the Talmudic community of medieval Europe

Eva de Visscher, University of Oxford

Jewish teachers, Christian pupils: the transmission of rabbinic learning from Jewish to Christian scholars in medieval England

Anna Abulafia, University of Cambridge

Notions of Jewish service in twelfth and thirteenth-century England.

Robert Stacey, University of Washington

The Massacres of 1189-90 and the Origins of the Jewish Exchequer, 1186-1226

Robin Mundill, Glenalmond College, Perth

The Legacy of the Archa System after 1216.

Matthew Mesley, University of Exeter

Cures and Conversions: The ‘Jewish Pilgrim topos’ in 13th century miracle accounts.

Carlee Bradbury, Radford College

“Monstrous contact: the Jew at the funeral of the Virgin Mary.”

Hannah Johnson, Pitt University, US

Massacre and Memory: The New Intellectual Politics of Remembering Jewish Martyrdom”

Jeffrey Cohen, George Washington University, US

The Future of the Jews of York

Anthony Bale, Birkbeck College, London

Text, Memory, Event: The Aesthetics of Persecution

Thursday, 29 April 2010

What next?

It has taken me a month to get back to 1190 - ('events, events' is possibly the best explanation of that) - but that has also given Sethina and I a chance to reflect on the conference and consider better what to do next.

The importance of holding the conference in York struck us more forcibly during the conference than it ever had done even in the two long years planning it - and the patterns, interconnections, and even tensions that emerged between the papers really did mean that for us the 'whole was more than the sum of its parts'. So - we both found the conference immensely thought-provoking - but also, can I say, good fun, making firm friends (we hope!) with so many people who had just been names before.

The most immediate answer to the question of 'what next?' is publication. We have identified one or two gaps in the programme which we think need filling in the book, but we are writing to people individually about that. So if you have not heard from us already, you will very soon!!

Otherwise our plan is to move ahead slowly (ish). We both feel that the social life of towns, and of neighbourliness, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and of the intersections of faith with other sources of identity and change, deserve more work - and we intend to build on that after the conference book is completed. We will certainly want to think about the 'impact' that has in terms of the profile of 1190 in York as well as outside (and Ian Bloom's piece below is very useful for cautioning us about how to think about that). We'd welcome your thoughts and suggestions, discussion, ideas, comment.

Otherwise we're very happy for you to use the blog for any discussion or comment of your own.

The picture is of Sopron, Hungary - famous for its twelfth-century fire tower, and synagogue, among many historic monuments (and which i hope to visit soon!).

The importance of holding the conference in York struck us more forcibly during the conference than it ever had done even in the two long years planning it - and the patterns, interconnections, and even tensions that emerged between the papers really did mean that for us the 'whole was more than the sum of its parts'. So - we both found the conference immensely thought-provoking - but also, can I say, good fun, making firm friends (we hope!) with so many people who had just been names before.

The most immediate answer to the question of 'what next?' is publication. We have identified one or two gaps in the programme which we think need filling in the book, but we are writing to people individually about that. So if you have not heard from us already, you will very soon!!

Otherwise our plan is to move ahead slowly (ish). We both feel that the social life of towns, and of neighbourliness, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and of the intersections of faith with other sources of identity and change, deserve more work - and we intend to build on that after the conference book is completed. We will certainly want to think about the 'impact' that has in terms of the profile of 1190 in York as well as outside (and Ian Bloom's piece below is very useful for cautioning us about how to think about that). We'd welcome your thoughts and suggestions, discussion, ideas, comment.

Otherwise we're very happy for you to use the blog for any discussion or comment of your own.

The picture is of Sopron, Hungary - famous for its twelfth-century fire tower, and synagogue, among many historic monuments (and which i hope to visit soon!).

Monday, 26 April 2010

Thursday, 8 April 2010

Jewish News 1st April 2010

I was offered 300 words by the Jewish Chronicle but 700 - and a picture - by the Jewish News for an account of the Conference. So of course I chose the latter. You can find my piece on line at:

www.totallyjewish.com and then you have to navigate your way into the most recent back issue dated 1st April 2010 and find page 12. Sadly the word limit did not allow space for tributes to Barrie Dobson or Sarah and the team who organised the event or to the speakers by name. But at least the fact that the Conference took place and an outline of what was discussed has reached those members of the Jewish community who read that issue.

www.totallyjewish.com and then you have to navigate your way into the most recent back issue dated 1st April 2010 and find page 12. Sadly the word limit did not allow space for tributes to Barrie Dobson or Sarah and the team who organised the event or to the speakers by name. But at least the fact that the Conference took place and an outline of what was discussed has reached those members of the Jewish community who read that issue.

Monday, 5 April 2010

Thursday, 1 April 2010

Jewish Telegraph

The Jewish Telegraph (Manchester, 26 March 2010) has a double-page spread on the conference by Yaakov Wise. I cannot find it online. It includes synopses of many of the papers.

Tuesday, 30 March 2010

The History of Clifford's Tower between 1190 and 1245

Jonathan Clark's report, as sent by Jeremy Ashbee, English Heritage. I am afraid these refuse to be emailed. There is a longer technical report. I post only the shorter version here:

One topic which has hitherto received little discussion is the development of the site of Clifford’s Tower between 1190 and the construction of Clifford’s Tower itself, now generally accepted to have begun in 1245. An assessment of whether any significant archaeological remains of the events of 1190 are preserved on the site is essential for the formulation of policy concerning its future management.

The chronicle sources do not give consistent accounts of the extent of destruction after 1190, and none of them explicitly states that the tower in which the Jews had hidden was destroyed or unusable after the event. However, evidence of expenditure in works on the castle of York, recorded in the Pipe Rolls, strongly suggests that the building was badly damaged if not destroyed. The crucial entries are in the Pipe Rolls for years 2 and 3 of Richard I, amounting to £219, and include the expenditure of over £179 in the first six months after the massacre (ie before the Michaelmas 1190 session of the Exchequer). The inevitable conclusion is that these works were brought on by damage during the siege of 1190.

The generally accepted interpretation of the documentary record is that the tower in which the Jewish community took refuge was replaced by another timber building. The fate of this is unknown. However, since other buildings in the castle are known to have been destroyed by high winds in 1228.it has sometimes been assumed that a timber tower on the motte would inevitably, by virtue of its exposed site, have been lost at the same time. This inference is logical but ultimately cannot be confirmed on present evidence.

Excavations have been carried out on the motte both inside and outside Clifford’s Tower, notably in 1902, when a stratigraphic sequence for the build-up of the motte was established by a trench and borehole within the area of the keep. Of the many discoveries made during these works, two are of particular relevance for the history of the site prior to the construction of Clifford’s Tower.

The first was that the motte had been heightened by some 13 feet in material described as ‘an outer crust of firmer and more clayey material’, with lighter material (‘reddish gravel’) added on the top to bring the motte’s summit up to its present level: the uppermost levels are confusingly labelled in a cross-section drawing as ‘black soil.’ The date of this heightening is debatable: the foundations of Clifford’s Tower are shown penetrating into this layer, but the drawings are not sufficiently detailed to show whether they sit within a construction trench cut through it. (A suggestion that they do is given in the accompanying text:- ‘the walls of the keep go down to a depth of 6 ft and the foundations, 11 ft wide, rest on a bed of puddled clay 1 ft deep.’) The interpretation followed by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments is that this heightening occurred in the 1240s, immediately before the construction of Clifford’s Tower. However, the evidence cited above suggests strongly that the heightening took place some time before work began on Clifford’s Tower. It may be noted that the Pipe Roll entry for Michaelmas 1190 indicates that work had been carried out on the motte (mota).

The second archaeological discovery made in 1902 is that the motte contains traces of timbers, at approximately 15 and a half feet, and 13 feet below the present ground level. The upper timbers formed a platform, 6 inches thick, overlying 2 ft 6 inches of black clay, under which were discovered ‘the remains of a similar oak platform supported by posts.’ These were interpreted as the products of two distinct episodes. It was remarked that large quantities of charred wood were found above the lower timbers, interpreted by the excavators as the remains of a wooden tower of 1068, burnt during the northern rebellion of 1069. An alternative reading is to see the burnt timbers as remains of the building destroyed in 1190, and the upper tier of timber as the footings of a replacement building. Other structures included a ‘wooden boatstay, evidently of great age’.

During the excavations of 1902, and during an investigation of the motte in 1824, human bones were discovered. These have been variously interpreted as Roman or Prehistoric, and some of them are believed to be redeposited in the upcast from the ditch around the motte. The existing record does not allow any statement of the relationship between human bones and the burnt timbers mentioned above. It is simply stated that ‘a large number of bones was found in every part of the mound. Human bones were abundant, especially in the interior of the keep.’

In conclusion, there is insufficient evidence to associate any of the archaeological remains within the motte at Clifford’s Tower with the massacre of 1190 and its aftermath. However, it is clear that the motte is a complex structure incorporating the remains of several phases of occupation. The documentary and archaeological records also suggest that its history is one of accretion and build-up. This leaves open the possibility, perhaps even probability, that in the months after March 1190, some of the debris from the destruction of the tower was buried within the motte. The possibility of cremated human remains being preserved inside the motte likewise remains open.

One topic which has hitherto received little discussion is the development of the site of Clifford’s Tower between 1190 and the construction of Clifford’s Tower itself, now generally accepted to have begun in 1245. An assessment of whether any significant archaeological remains of the events of 1190 are preserved on the site is essential for the formulation of policy concerning its future management.

The chronicle sources do not give consistent accounts of the extent of destruction after 1190, and none of them explicitly states that the tower in which the Jews had hidden was destroyed or unusable after the event. However, evidence of expenditure in works on the castle of York, recorded in the Pipe Rolls, strongly suggests that the building was badly damaged if not destroyed. The crucial entries are in the Pipe Rolls for years 2 and 3 of Richard I, amounting to £219, and include the expenditure of over £179 in the first six months after the massacre (ie before the Michaelmas 1190 session of the Exchequer). The inevitable conclusion is that these works were brought on by damage during the siege of 1190.

The generally accepted interpretation of the documentary record is that the tower in which the Jewish community took refuge was replaced by another timber building. The fate of this is unknown. However, since other buildings in the castle are known to have been destroyed by high winds in 1228.it has sometimes been assumed that a timber tower on the motte would inevitably, by virtue of its exposed site, have been lost at the same time. This inference is logical but ultimately cannot be confirmed on present evidence.

Excavations have been carried out on the motte both inside and outside Clifford’s Tower, notably in 1902, when a stratigraphic sequence for the build-up of the motte was established by a trench and borehole within the area of the keep. Of the many discoveries made during these works, two are of particular relevance for the history of the site prior to the construction of Clifford’s Tower.

The first was that the motte had been heightened by some 13 feet in material described as ‘an outer crust of firmer and more clayey material’, with lighter material (‘reddish gravel’) added on the top to bring the motte’s summit up to its present level: the uppermost levels are confusingly labelled in a cross-section drawing as ‘black soil.’ The date of this heightening is debatable: the foundations of Clifford’s Tower are shown penetrating into this layer, but the drawings are not sufficiently detailed to show whether they sit within a construction trench cut through it. (A suggestion that they do is given in the accompanying text:- ‘the walls of the keep go down to a depth of 6 ft and the foundations, 11 ft wide, rest on a bed of puddled clay 1 ft deep.’) The interpretation followed by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments is that this heightening occurred in the 1240s, immediately before the construction of Clifford’s Tower. However, the evidence cited above suggests strongly that the heightening took place some time before work began on Clifford’s Tower. It may be noted that the Pipe Roll entry for Michaelmas 1190 indicates that work had been carried out on the motte (mota).

The second archaeological discovery made in 1902 is that the motte contains traces of timbers, at approximately 15 and a half feet, and 13 feet below the present ground level. The upper timbers formed a platform, 6 inches thick, overlying 2 ft 6 inches of black clay, under which were discovered ‘the remains of a similar oak platform supported by posts.’ These were interpreted as the products of two distinct episodes. It was remarked that large quantities of charred wood were found above the lower timbers, interpreted by the excavators as the remains of a wooden tower of 1068, burnt during the northern rebellion of 1069. An alternative reading is to see the burnt timbers as remains of the building destroyed in 1190, and the upper tier of timber as the footings of a replacement building. Other structures included a ‘wooden boatstay, evidently of great age’.

During the excavations of 1902, and during an investigation of the motte in 1824, human bones were discovered. These have been variously interpreted as Roman or Prehistoric, and some of them are believed to be redeposited in the upcast from the ditch around the motte. The existing record does not allow any statement of the relationship between human bones and the burnt timbers mentioned above. It is simply stated that ‘a large number of bones was found in every part of the mound. Human bones were abundant, especially in the interior of the keep.’

In conclusion, there is insufficient evidence to associate any of the archaeological remains within the motte at Clifford’s Tower with the massacre of 1190 and its aftermath. However, it is clear that the motte is a complex structure incorporating the remains of several phases of occupation. The documentary and archaeological records also suggest that its history is one of accretion and build-up. This leaves open the possibility, perhaps even probability, that in the months after March 1190, some of the debris from the destruction of the tower was buried within the motte. The possibility of cremated human remains being preserved inside the motte likewise remains open.

The Future of the Jews of York

I just place a draft of my talk up at In the Middle, for anyone who is interested.

The Stiffnecked

Along the same lines as Robert's post on Blindness and the figure of Synagoga, and here seeking the stereotypes that underpin William of Newburgh's use of 'rigidi' for the Jews of 1190, does anyone know of a treatment in the secondary literature of the idea of the Jews as a 'stiff-necked' people, dervied from Exodus 32:9, where God himself is reported as declaring 'Populus iste durae cervicis sit' ?

Monday, 29 March 2010

Clifford's Tower: archaeology

From Jeremy Ashbee, Head Properties Curator, English Heritage.

Jeremy has kindly supplied the archaeological appraisal of Clifford's Tower which, with his permission, I will email to delegates later this week. He adds:

"Jonathan Clark is currently at an advanced stage of re-writing the EH guidebook for Clifford's Tower, to be published this summer, and I know he develops some of his theories about whether Henry III's building incorporated earlier structures - he hadn't got to this stage when he wrote his archaeological appraisal, so I'd be grateful if you could put in a line that more information relevant to the castle of 1190 and its aftermath will be available shortly."

I think this means a return trip for you all to York this summer ;-)

Jeremy has kindly supplied the archaeological appraisal of Clifford's Tower which, with his permission, I will email to delegates later this week. He adds:

"Jonathan Clark is currently at an advanced stage of re-writing the EH guidebook for Clifford's Tower, to be published this summer, and I know he develops some of his theories about whether Henry III's building incorporated earlier structures - he hadn't got to this stage when he wrote his archaeological appraisal, so I'd be grateful if you could put in a line that more information relevant to the castle of 1190 and its aftermath will be available shortly."

I think this means a return trip for you all to York this summer ;-)

Sunday, 28 March 2010

Bury St Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds massacre

A few links for those who expressed interestBury St Edmunds

link http://www.jtrails.org.uk/trails/bury-st.-edmunds/places-of-interest

http://www.jewishgen.org/JCR-uk/pre-1290/1290communities/east1290.htm#bury1290

http://www.information-britain.co.uk/famdates.php?id=901

A few links for those who expressed interestBury St Edmunds

link http://www.jtrails.org.uk/trails/bury-st.-edmunds/places-of-interest

http://www.jewishgen.org/JCR-uk/pre-1290/1290communities/east1290.htm#bury1290

http://www.information-britain.co.uk/famdates.php?id=901

Fee debts and Bowie bonds

The practice of advancing money on an annuity was just one mechanism that came into play in the mid-thirteenth century. A fee debt, as defined by Dr Sharon Lieberman, was a perpetual agreement to alienate or give the revenue which came from a portion of land in exchange for a cash advance.

They were later banned by the Provisions of the Jewry in 1269

“…for the better ordering of the land and the relief of the Christians from the burdens laid upon them by the Jewry of England: that all debts to Jews which are fees, and which are at present in the hands of the Jews are not assigned or sold to Christians,………….and let no Jew from this day forth take or make any such fee debt.

The problem seems to have been that there was a market in such bonds and they were being sold on. In the 1260s some debtors were also providing annual lump sums for cash in advance and these were being sold on on the open market. As early as June 1267, Robert Burnell tried to benefit from the market in fee debts when Master Elias Menahem granted him two yearly fees worth £31 'with the usuries and penalties'.

Today in the light of Lehmann brothers we might well notice the parallel of this type of securitisation which more recently has been associated with the Pullman or Bowie Bond. In 1997 the Prudential paid $55 million for the future revenues of 25 David Bowie Albums. These Bowie bonds were sold on and traded on. In January last year Evan Davis and others looked into this practice

http://www.mirror.co.uk/celebs/news/2009/01/12/david-bowie-s-back-catalogue-bonds-may-have-started-the-credit-crunch-115875-21036649/

http://new.uk.music.yahoo.com/blogs/guestlist/14935/did-david-bowie-cause-the-credit-crunch

They were later banned by the Provisions of the Jewry in 1269

“…for the better ordering of the land and the relief of the Christians from the burdens laid upon them by the Jewry of England: that all debts to Jews which are fees, and which are at present in the hands of the Jews are not assigned or sold to Christians,………….and let no Jew from this day forth take or make any such fee debt.

The problem seems to have been that there was a market in such bonds and they were being sold on. In the 1260s some debtors were also providing annual lump sums for cash in advance and these were being sold on on the open market. As early as June 1267, Robert Burnell tried to benefit from the market in fee debts when Master Elias Menahem granted him two yearly fees worth £31 'with the usuries and penalties'.

Today in the light of Lehmann brothers we might well notice the parallel of this type of securitisation which more recently has been associated with the Pullman or Bowie Bond. In 1997 the Prudential paid $55 million for the future revenues of 25 David Bowie Albums. These Bowie bonds were sold on and traded on. In January last year Evan Davis and others looked into this practice

http://www.mirror.co.uk/celebs/news/2009/01/12/david-bowie-s-back-catalogue-bonds-may-have-started-the-credit-crunch-115875-21036649/

http://new.uk.music.yahoo.com/blogs/guestlist/14935/did-david-bowie-cause-the-credit-crunch

Saturday, 27 March 2010

Blindness – a medieval preoccupation and fascination?

Robin Mundill asked the following question:

In relation to the Jews it was during Carlee Bradbury’s paper that I thought of the panel from the York Chapter House roof and the depiction of Synagogue. Is it coincidence that the blind woman involved in the ritual murder story of St Hugh was healed? The language of Edward’s strengthening of the London Domus Conversorum in 1280 reads “ in order that those who have already turned from their blindness to the light of the Church…….’. Or am I reading too much into it?

In relation to the Jews it was during Carlee Bradbury’s paper that I thought of the panel from the York Chapter House roof and the depiction of Synagogue. Is it coincidence that the blind woman involved in the ritual murder story of St Hugh was healed? The language of Edward’s strengthening of the London Domus Conversorum in 1280 reads “ in order that those who have already turned from their blindness to the light of the Church…….’. Or am I reading too much into it?

(Robin I moved this from the comments to a New Post - I think it will attract more discussion that way).

In relation to the Jews it was during Carlee Bradbury’s paper that I thought of the panel from the York Chapter House roof and the depiction of Synagogue. Is it coincidence that the blind woman involved in the ritual murder story of St Hugh was healed? The language of Edward’s strengthening of the London Domus Conversorum in 1280 reads “ in order that those who have already turned from their blindness to the light of the Church…….’. Or am I reading too much into it?

In relation to the Jews it was during Carlee Bradbury’s paper that I thought of the panel from the York Chapter House roof and the depiction of Synagogue. Is it coincidence that the blind woman involved in the ritual murder story of St Hugh was healed? The language of Edward’s strengthening of the London Domus Conversorum in 1280 reads “ in order that those who have already turned from their blindness to the light of the Church…….’. Or am I reading too much into it?Friday, 26 March 2010

Thursday, 25 March 2010

York 1190 in 2010

In March 2010 we held a conference at the University of York: 'York 1190: Jews and Others in the Wake of Massacre'. It was attended by around 84 people from three continents - and over three intense days we shared some really thought provoking academic papers, discussion, beer and two harrowing (but wonderfully performed plays). Barrie Dobson was presented with a volume of his collected works on medieval English Jewish communities by Joe Hillaby.

Robin Mundill suggested that it would be good to have a forum where the discussion could continue. So here it is!

It was an extremely rich three days for me - and it will take me a long time to absorb it all. Nick and Hugh have now confirmed that my (and Birch's) reading of the seal legend is indeed correct. The first common seal of the City of York does indeed bear the legend 'Fideles Regis' - quite chilling in the immediate aftermath of 1190 - but more on that to come in publications, I am sure.

Robin Mundill suggested that it would be good to have a forum where the discussion could continue. So here it is!

It was an extremely rich three days for me - and it will take me a long time to absorb it all. Nick and Hugh have now confirmed that my (and Birch's) reading of the seal legend is indeed correct. The first common seal of the City of York does indeed bear the legend 'Fideles Regis' - quite chilling in the immediate aftermath of 1190 - but more on that to come in publications, I am sure.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)